Musical Rests

I often think of my dad when I hear music, when I make music, or even just when I experience the sounds around me. Music was one of the strongest connections we had.

He would have loved options like Spotify, giving him the ability to select exactly what he wanted to listen to at any moment. I enjoy being able to shift my mood when driving, writing, working, or doing household tasks just by changing up the musical background.

Still, sometimes what I want and need most is silence—or maybe just quiet. Sometimes I just need less so that I can hear more.

My dad used to talk about the silence within music. As a musician, he taught me the importance of observing rests, of lingering over them sometimes as I play a piece of music, helping a listener to wait, to anticipate, to reflect on what they have just heard. He told me that in that pause, we also help the listener hear the next note differently.

I like it when a musician plays with the rests, holding a pause a little longer than expected. When I attend a classical concert, I love it when the audience waits a bit to applaud after a piece, the conductor’s raised arms signaling that we will all collectively breathe in this extended pause, letting the music’s final chord linger in our minds.

Like the white space between paragraphs, that pause gives me time to think. And my dad was correct—it helps me hear what comes next in a different way.

Perhaps the most profound experience I ever had with music, silence, and sound was over 20 years ago. While I was working on my PhD in English at Loyola University in Chicago, I was fortunate enough to receive a research fellowship for one semester. That meant they paid my tuition and gave me a small stipend in exchange for my helping a professor with their research. The faculty member I worked with was amazing, inviting me to co-author a piece with him that ended up being my first professional publication.

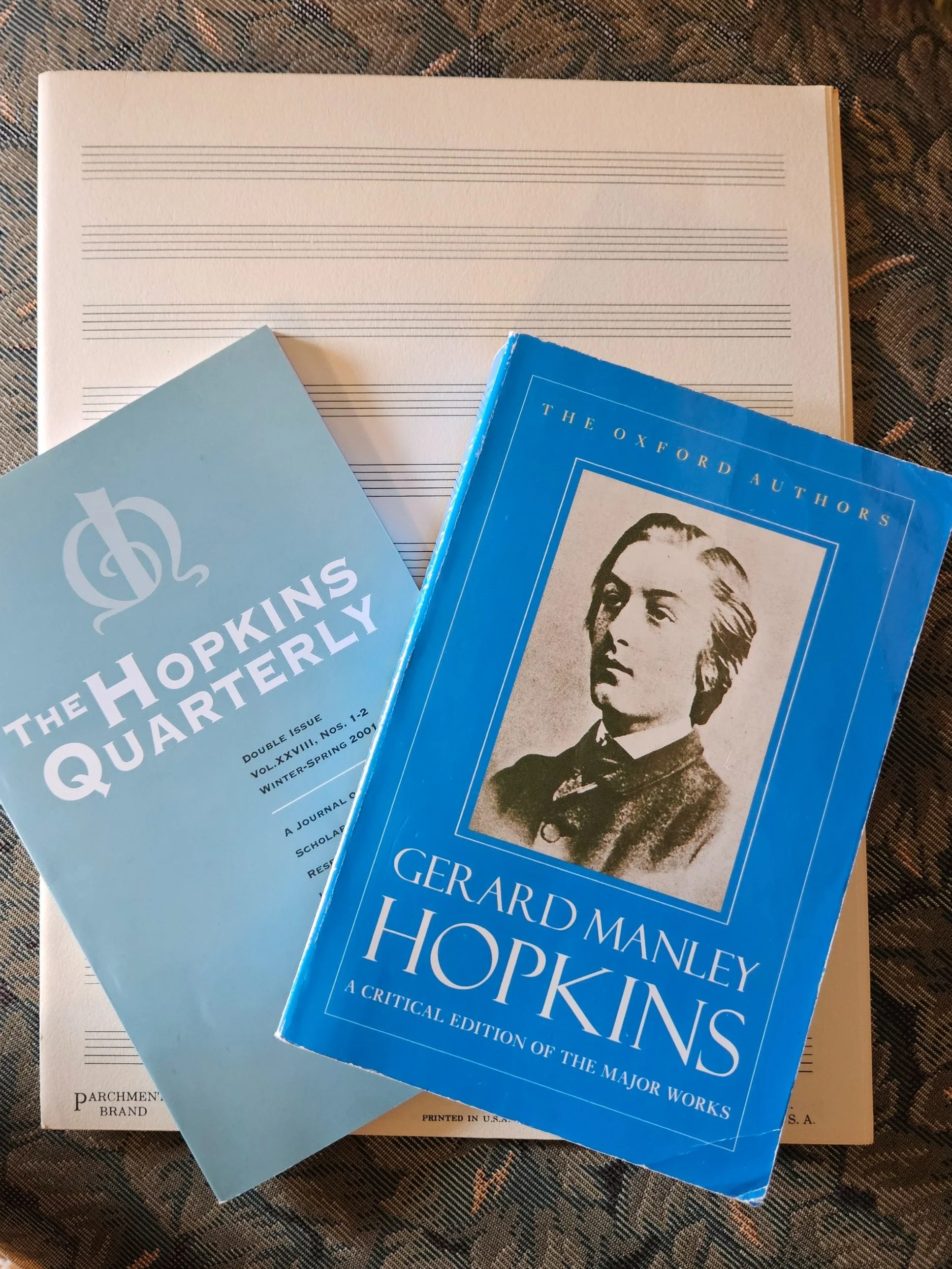

We were a good team. He was an expert in the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, a 19th century poet who experimented a lot with rhythm and sound. My professor’s focus for this project was on composers who took Hopkins’ poetry and set it to music. I brought to the partnership an ability to read and interpret scores when we couldn’t find a recording of a piece of music, as well as enough musical background that I could write some reasonably clear observations about connections between the words Hopkins wrote and the musical choices of different composers.

I spent a fair bit of time that semester in the music library at Northwestern University in Chicago, listening to music and reading scores. One afternoon, towards the end of my time at the library, I listened to a recording of a piece supposedly inspired by Hopkins’ poetry, especially by his idea of “inscape.” Hopkins’ poetry can be difficult to understand, in part because he really wanted it to be read aloud and for people to focus as much on how it sounded as on what it meant, and sometimes people don’t know that when they encounter it. Plus, Hopkins was a deep thinker. He wanted people to focus on the essence of a thing (a tree, a leaf, a person), all its complexity, all that makes it unique—and see how it connected with everything else in the world. I don’t feel like I ever fully understand a Hopkins poem when I read it aloud, but I feel something from the sounds, and I am challenged by his phrases and images.

At any rate, this piece called “Three Inscapes” was composed by Douglas Lilburn from New Zealand. The recording was from 1972. It was supposedly inspired by Hopkins’ poetry.

And it was weird. To my ear trained by my dad to love Bach, Beethoven, and Tchaikovsky, it didn’t feel like music. It didn’t fit the parameters of the 70s and 80s rock I grew up listening to either.

I remember feeling like I had to survive the full recording made by some electronic instrument, probably an early synthesizer. It had one super long note that slowly overlapped with other pitches, some of which just didn’t seem to fit. It had noises in it that felt like the whirs and clicks of the 1990s when I tried to log on to the internet. It felt like just static at times, chaotic, but not in a frenzied way. It was slow. Just notes and noises. No melody or harmony. Nothing you could walk away humming. And sometimes, it contained random pauses, random bits of silence when I thought it was done, but it wasn’t.

I left the library that day feeling rather disgusted. “What a waste of time,” I thought. “Who thought that was music?”

Before heading back towards my apartment via the train, I decided to stop in the bathroom. I was the only one in there as I opened the door, so it was silent inside. I heard my feet move across the floor. I heard the door to the stall swing shut. I heard the click of the metal lock. Moments later as I turned on the faucet, I heard the metal on metal as I turned the knob. I heard the water. I tore off a sheet of paper towel and heard it.

I heard all these noises in a way I never had. I stood in that bathroom alone and looked around. I’m confident had someone come in at that moment and seen the confused look on my face they would have been concerned. All I could think was, “What is happening to me? Why does everything sound...so...much?”

As I re-entered the world outside the library building, as I walked the blocks to the train station, as I waited for and boarded the subway train to start my commute back, as I heard people enter and leave the car I was in, I couldn’t stop hearing the world around me. I couldn’t stop hearing the music—the different pitches of sounds and the way they intermingled. The screech of the train wheels on the rails was suddenly not just noise, but more like atonal music. Whooshes and squeaks and shuffles all came alive in a new way. I could hear the world’s sounds and music better because I could separate and distinguish among all the different sounds. I could hear the breaks in sound—the gaps between, the rests.

It dawned on me later that the composer’s impact on me had been more profound than most. In those long stretches of sound, the composer had forced me to slow down my listening, to focus my ear and my attention. They had forced me to center on a pitch, to study it from different and new angles, such that every note of the world came alive for me. I shared with my professor that in some ways I felt this composer had understood Hopkins’ desire to get people to slow down and focus on the sounds of words and the world better than any of the other composers. In some ways, he had helped me understand something elusive about Hopkins’ purpose where other composers had failed. Since Hopkins was also very religious and spiritual, the whole experience feeling transcendent and focused fit his mission as well.

I don’t remember most of the other musical settings of his poetry that I listened to that semester. But I will never forget my experience with that strange piece of music. The effect it had lasted several hours and the memory lingers decades later. I can’t say I “liked” the piece, but that wasn’t the point. It challenged me and challenges me still to think differently.

Sometimes I try to recapture that focus on sounds around me. Sometimes I long for it in the same way that sometimes I long for silence.

Unlike my dad, who never got to experience a world with Spotify, I am two clicks away from any music I want to hear and yes, that helps me daily to focus, to improve my mood, and to enjoy life.

I wish I were also better at hearing the music hidden inside my everyday actions. I wish I were better at separating and distinguishing among the everyday noises, hearing the essence of something. The Victorian clock ticking in the other room. The motorcycle passing our house. The muffled sounds of my son’s voices upstairs playing a video game. The hum of the refrigerator. The clicking of the keys on my laptop.

In those moments, I can have it all—the music I love at the click of a button and the world’s music surrounding me. If I could listen that way more often, I would be able to find the silence more often too. I could reflect on concepts like inscape that escape our understanding and are, therefore, the truth we continue to seek. I could find the rests and breathe through them.