(Don’t) Call Me Doctor

I was at a meeting recently out in the community, representing my college employer. The paper name plate in front of me read “Dr. Jennifer Flatt.” I think everyone in the room knows my name already, but I know we all meet lots of people every week, so it’s nice at these larger meetings to have names right in front of everyone. Towards the end of the meeting, someone referenced something I’d said earlier. In doing so, he called me “Dr. Flatt.”

Immediately, as I usually do when this occurs, I felt worried. I held my breath. I wondered.

Does he think I asked for that to be on my name card? Does he think I am an arrogant, self-absorbed, pretentious snob who thinks I’m better than he is?

To most people outside my brain, that might seem like quite the leap in thinking! My thoughts might seem irrational. Maybe that’s true. Still, my immediate, almost paranoid reaction to being called “Dr. Flatt” in this public space is the result of a long personal history, one of trying to find a way to be proud of my accomplishments, a journey I think many people share.

On some level, I am proud of having completed my doctorate in English. I know what went into it. After finishing a double major in English and Spanish at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, I spent two years taking additional classes, teaching part-time, and working summers as a temp office worker to complete my master's degree in English at the University of Minnesota-Duluth.

I can reduce the next four years of struggle and hard work to just a few sentences:

I took highly focused doctoral classes in English literature for two years at Loyola University in Chicago while working part time jobs and teaching part-time.

I then spent six months studying for my comprehensive exams. I needed to be ready to answer essay questions of any kind in three main areas covering 90 different books (some novels, some critical theory, some history).

I spent a year and a half writing my dissertation—what ended up for me to be a 400+-page book (never published in its entirety) about a highly focused topic. I was working part-time and earned both research and dissertation fellowships.

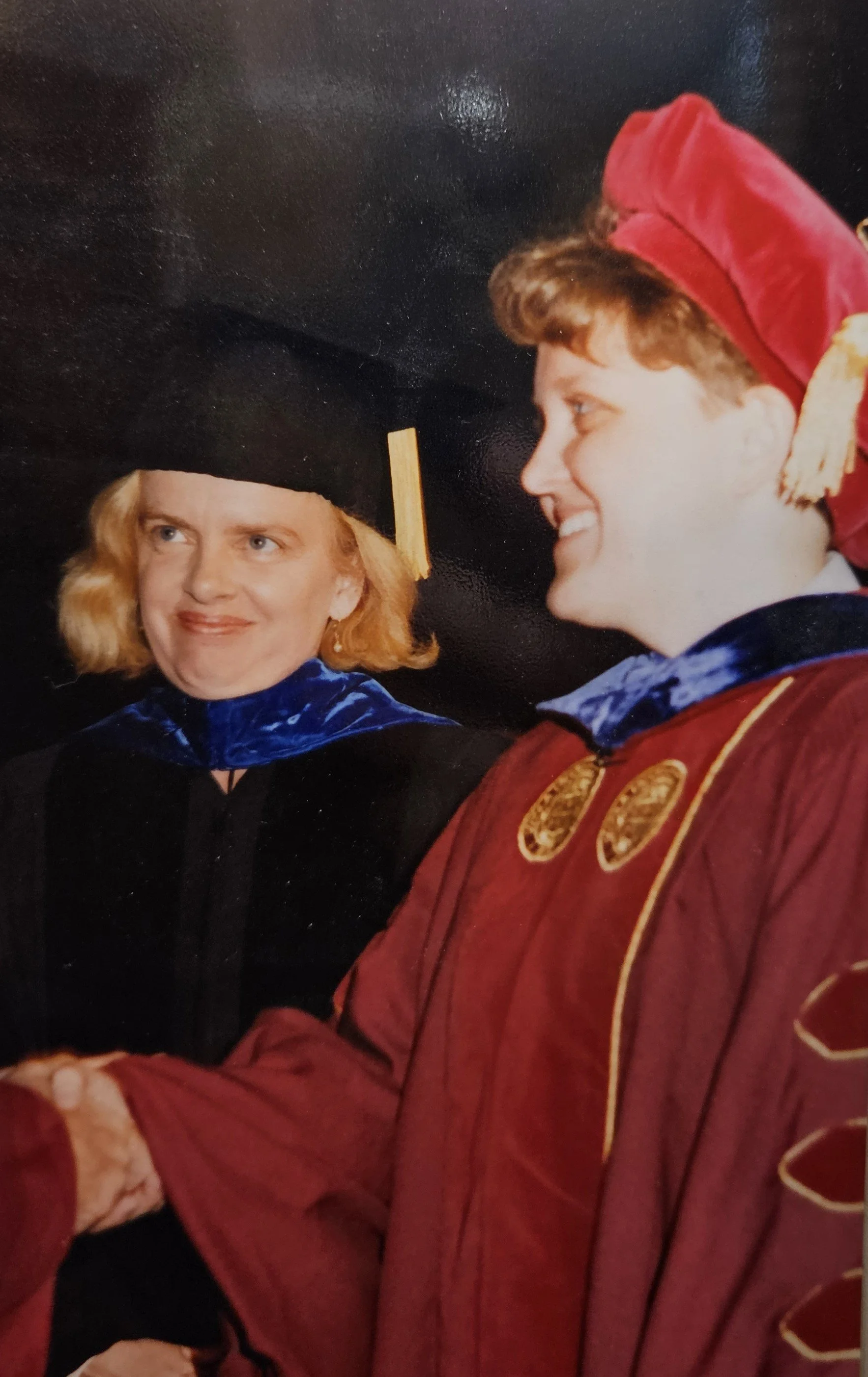

I’m on the right here—being congratulated by the president of Loyola University (Chicago). My dissertation advisor, Dr. Clarke, is on the left.

At the end of that road, I had a PhD (a Doctor of Philosophy) in English. “Philosophy” means “lover of wisdom” in ancient Greek. You probably do have to love wisdom and learning to spend six years after college in financially challenging situations continuing to be judged and graded as you try to find things to say that have never been said before (that’s the foundational prerequisite for a dissertation topic).

I don’t share this journey for sympathy or pity. I chose that path. It was hard. It got me what I wanted—a job teaching English at the college level. I have no regrets.

But I think I felt proud about being able to call myself Dr. Stolpa (at the time) for just a few months.

I was gifted an engraved nameplate that said “Dr. Jennifer Stolpa.” My family came to the graduation. The staff at the part-time job I was working at the time celebrated with me. Then I moved hundreds of miles away to begin my teaching career. I also began a journey where some voices questioned whether I should use my newly earned title.

“I just have my students call me by first name,” said a colleague early on. “It helps them feel more comfortable around me. You should do that too!”

“We won’t print your title in that newspaper article about your conference presentation, Jennifer,” shared the PR person on campus. “We don’t want the people in the town to feel like you think you’re better than they are. It would be bad for the college.”

“Why would I call you Dr.?” asked (many) a student. “You’re not a real doctor.”

In those situations, I tried explaining the difference between a medical doctor and a PhD. Some students understood. Many students called me Dr. Stolpa. Some called me Mrs. Stolpa even though I wasn’t married. Some called me Jennifer. As a 28-year-old woman, that led some students to start to talk to me as if we could be friends. I felt uncomfortable.

“You are hurting students by asking them to call you Dr. Stolpa,” one male colleague told me about three years into my teaching career. “You make them feel intimidated and they don’t want to come see you.” I knew that my office hours were always busy and students came to me all the time to tell me their fears and worries, but I doubted myself, wondering if my male colleague was right.

For a brief while, I considered asking students to call me “Dr. J.” Maybe people won’t mind if I use my title if I make it seem lesser with just my first initial. In the end, I didn’t feel cool enough or comfortable enough to do that.

When I met my husband and told him about all of this, he started to call me “Doctor” as a nickname. I know it was his way of making me feel more comfortable with it. He still does sometimes and I love him for it. Later, when he started teaching part-time at the same college where I was then an experienced, tenured full professor, we had some students in common. He told me one day about how this student insisted on calling him “Professor Flatt.”

“I’m not a professor,” he would tell her. “Please call me Jason or Mr. Flatt.”

“I can’t do that,” she said. “That just doesn’t feel comfortable for me.”

“Huh,” I said to Jason. “That’s funny and sad.”

“Why’s that?” Jason asked.

“Even though I’ve asked the class to call me Dr. Flatt, she calls me Mrs. Flatt. When I asked her why, she said she didn’t feel comfortable calling me Dr. Flatt.”

Clearly and not surprisingly there are gender issues at play here.

In my current role, as Vice President of Student Affairs at a technical college, my email signature reads “Jennifer Flatt, PhD.” I agonized over that decision. I have a name tag that says “Dr. Jennifer Flatt” and one that just says “Jennifer Flatt.” I almost never wear the first one.

The truth is that while I worked hard to earn a PhD, I didn’t let myself feel joy for long. And I don’t feel only pride when I hear someone call me Dr. Flatt.

I’d love to blame others for taking away that joy. That would be easier. And I do think there is some blame to be shared. No one should make someone question whether they can or should use a title they’ve earned. And I question if my journey would have been different over the years if I were a male medical doctor who introduced themselves as Dr. Flatt.

Still, I know that part of this is on me. For all the voices I reference above, there have been other voices—so many—who called me Dr. Stolpa or Dr. Flatt without hesitation, students who admired me for my accomplishments, and colleagues who encouraged me to use the title. Like with all criticism, it is up to me to focus my attention away from the few negative voices and towards the positive. It is up to me to have my own internal voice affirm my right to feel pride in my accomplishments.

I've never done so well with that. My senior year of high school, I earned many honors and accolades. I had worked very hard for four years. A week after graduating valedictorian, I wrote in my journal that my sense of pride had faded and was being replaced by fears of college—was I good enough?

Again, I could blame the voice I still hear in my head—the voice of a parent at the student awards ceremony my senior year as I walked past to collect what I’m sure felt to her like my millionth award: “Why does she get so many awards? They should spread them out more so she doesn’t keep going up there.” Yes, that woman could have done better in that moment. There was no need for her to try to make me feel guilty about my accomplishments.

But I need to stop listening to her.

I need to stop hearing her voice when the community member says “Like Dr. Flatt said earlier...”

I need to stop hearing those voices when I see an envelope arrive from my kids’ high school addressed to Dr. and Mr. Flatt. I need to work to just feel joy and pride.

Yes, I can be angry at those who diminished me or think I’m wrong for wanting to use a title I earned. But I should also be angry with myself for listening.

As I have been working on the pre-launch of my memoir, I have felt similar worries. Will people feel I am arrogant for talking about my book? How do I balance the feeling of pride I have with the humility my upbringing and the religion of my childhood tell me I should have? How can I learn from my past experiences and do better this time at allowing myself to feel pride?

I know I am not alone in these challenges. Unconsciously, at least I hope it’s unconsciously, we are taught and teach ourselves to stay in our place. We hold each other down without realizing it. And then when someone comes along and tries to lift us up, sometimes we’re not quite sure what to do with it.

How can we help each other to own the joy of our accomplishments more? I read a book recently where a group of female friends threw a party to celebrate the launch of a friend’s business and I loved that idea. Yet even in that book, the woman herself wasn’t sure she deserved it.

How do we help each other see that being proud of ourselves isn’t a bad thing?

I see the work I need to do. I need to continue to earn the title of Dr. Flatt in my own eyes. I need to hush the voices in my head when I hear the title and allow myself to feel joy and pride.

I’ll keep trying. And if you are in a meeting with me or you meet me, know that you can call me Jennifer. It’s my name and I’m proud of that too.

And know that if it feels appropriate to the moment and you call me Dr. Flatt, I will look at you and not look down (like I usually do). I will work hard not to assume you are thinking I am arrogant. I will take a deep breath and try to feel a sense of pride. Lots will be going on inside my mind as I will be working hard to grow. Thank you for helping me along. Let me know how I can help you too.